Settling Disputes or Disagreements

When to See An Arts Attorney

Artists who enter into significant or extended business relationships to either show, sell, commission, or reproduce their art are likely to benefit from occasional meetings with art attorneys. The preferred way to meet is before you formalize contracts, agreements, sign dotted lines or even shake hands. The less preferred way, regardless of how rosy the prognosis, is to wait until after a relationship has begun, and the really less preferred way is to wait until it's too late and the relationship is deteriorating.

Before starting any business relationship, however, and before your first face-to-face meeting with an attorney, a good idea is to learn a bit about how the legal side of the art business works. Read a book or two, read Common Artist Legal Problems and How to Avoid Them , ask other artists about legal problems they've either had or avoided, and attend workshops on legal issues for artists (see links below for California, New York and Chicago, IL attorney associations). Use these experiences to get an idea of what legal precautions you may have to take according to where you want to go with your art career and what you want to do with your art. Keep in mind that books, articles and conversations with other artists are not meant to substitute for actually meeting with attorneys or attending workshops on legal issues, but they certainly help you figure out what you'll want to learn once you get there.

The best time to see an attorney is when you have a contract, agreement or written conditions of an impending relationship in hand, but BEFORE you sign anything. At this point, you have no dispute, no obligation and nothing at stake. An advance meeting is recommended if you're just starting out, are inexperienced at negotiation, have little or no business experience or do not understand specific clauses or language in a contract or arrangement. An attorney can review your documents, point to areas of potential ambiguity, conflict, misunderstanding, or content that needs to be added, and in the process, help you avoid big problems later. Spotting potential trouble spots ahead of time is far less expensive, traumatic and time consuming than trying to resolve differences after the fact.

As far as etiquette goes, best procedure is keep any contacts with an attorney to yourself, especially if a meeting is merely to make sure a contract is reasonable or an agreement is fair. Announcing the fact that you're consulting an attorney is not something a gallery, agent or representative generally wants to hear, and you certainly don't want to give the impression that you don't trust them or have litigious inclinations. So play it safe and keep it low-key unless a situation deteriorates to a point where you have no other choice.

Since various attorneys specialize in various aspects of the arts, you first need to determine which type of attorney you need. Contact a nonprofit lawyer referral service such as Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts in New York City, Lawyers for the Creative Arts in Chicago or California Lawyers for the Arts with offices in Los Angeles, San Francisco and Sacramento (similar legal services are available in other parts of the country as well), describe your situation, and let them make recommendations. You can count on a referral service to give good solid advice. If, for example, they tell you that you don't need an attorney yet, then you probably don't need one. If you do need one, a typical half-hour meeting with a referred attorney is usually available for a nominal fee from nonprofit organizations like those mentioned above.

In most cases, nonprofit services are more than adequate for providing you with the advice you need. Using attorneys in the private sector makes sense if you already know or are referred to a private one, are negotiating very substantial or complicated issues, or are an experienced artist well along in your career and in need of regular legal services. Attorneys affiliated with nonprofits tend to be more generous with their time and advice, less inclined to advise legal action, and more affordable than their private sector counterparts.

Consult an attorney is also a good idea if you aren't given a contract, but are instead asked by the other party to supply your own contract, that contracts or agreements are not necessary, or that a handshake and verbal understanding will suffice. This is assuming that you haven't done business together before and do not have a previously established relationship The attorney will either advise or help you draft a contract or written agreement according to the specifics of your situation that you can then present to the other party. If you're a more experienced artist and you've negotiated similar situations before and have a standard agreement, then an attorney may not be necessary. But if any aspects of an arrangement (or lack of one) are unique, different, unclear, or new, then having an attorney review them with you is highly recommended.

No matter what type of business agreement you need, DO NOT copy a standard agreement out of a book, workshop, or seminar, and use it for your contract. Template contracts are good for learning basic contract structure and wording as well as for understanding the major aspects of a relationship that need to be covered, but may be not be appropriate for your specific situation or may completely leave out important details that are unique to your impending relationship. Only use form contracts when you really know what you're doing, you've done it before, know how to adjust the wording accordingly, and you completely understand what the other party wants. If an important detail gets overlooked or left out of the contract, then you leave yourself open to potential misunderstandings, disagreements, or problems later.

***

In situations where a relationship begins to break down or get difficult, do whatever you can to settle differences with the other party on your own first. Consulting or involving attorneys immediately after problems start is not advisable as long as there's hope you can resolve things yourself. Going legal should always be a last resort. But if that's your only option, meeting with an attorney recommended by an appropriate non-profit referral service is generally better than searching for one in the private sector unless you know exactly who or what you're looking for.

Start out by using the attorney as a sounding board to talk things through and explore reasonable non-legal solutions to the problem. Don't instantly insist that they make demands, draft and send intimidating letters, or make threatening phone calls. Explore non-confrontational approaches first and save the drastic stuff for later. A good attorney often knows ways to defuse and resolve sensitive situations and help you mediate your way through.

Whatever you decide, always do the money math first. You'll be surprised how expensive taking legal action can get, and how fast your money can vanish. So make sure you can afford to do whatever you want to do, and think long and hard about whether the costs will be worth the outcome.

Go slow, be patient, and most importantly, always allow time for your anger or frustration to dissipate before engaging with the other party. Put things in their proper perspective and evaluate what's really at stake; most problems are not life-or-death matters when you really take the time to think about them. Don't let ego or pride govern your actions either, especially when not that much money is at stake. Going that route can be extremely expensive, not cost-effective, miserable, exhausting, and a monumental waste of time.

To repeat-- no matter how unpleasant your situation is or how badly you want to take serious action or have an attorney take it for you, be patient. Whatever you do, don't threaten and don't escalate. The biggest mistake you can make is getting too antagonistic too fast and acting out of anger or emotion, not rationality and reason. Plenty of lawyers are willing to club the opposition on your behalf, but clubbing can easily spin out of control and turn a resolvable disagreement into an impossible dispute.

If you've reached an impasse or are too upset to speak calmly with the other party for any length of time, think about using a mediator to help work things through. Names of mediation services are usually available through nonprofit arts attorney associations. Be clear that you are not trying to force matters, but are rather reaching out, and trying to make things better by offering up a compromise. A mediator's job is to be neutral and to settle problems equitably. If warranted, hopefully you can find one you both agree on.

The big advantages of mediation are that it's far less expensive than attorneys and can be done outside of the legal system. Attorneys can easily bill $5,000-$10,000 or more per month, and going through the court system is just about the last thing you want. Mediation may be difficult at times, but it's far more affordable and often highly productive. As long as there's still hope, encourage the other party to mediate.

If a situation deteriorates to the point where resolution no longer seems possible, continue to use lawyer referrals and consultations as reality checks, not as preparations for war. Get clear on the pros and cons of your case, and on what you have to win or lose by going legal. If you decide to fight, you should have no problem finding an attorney to do so on your behalf and work according to your agenda (as long as you pay the bills). Know going in though, that the more you learn about how the legal system works, the more you come to realize that litigation is really expensive and that regardless of how things turn out, you'll likely get very little satisfaction in the end. Unless large amounts of art or money are involved, sometimes it's better to just plain walk away.

In the end, the best approach may be to view a disagreement as a growth opportunity rather than as a win-lose situation. Do what you can to work through problems as best you can, know when to let things go, and use the resulting lessons to become more savvy as an artist and businessperson when the next opportunity comes around. That way, even if you come up short, you still come out on top. Plus you'll have loads more time to spend on positive things like your art and artistic life.

Thanks to Nate Cooper, lawyer, mediator, musician, and former Legal Services and Education Coordinator for California Lawyers for the Arts, for assistance with this article.

Disclaimer: If you need legal help, see an attorney. This article is not to be taken or construed in any way as legal advice.

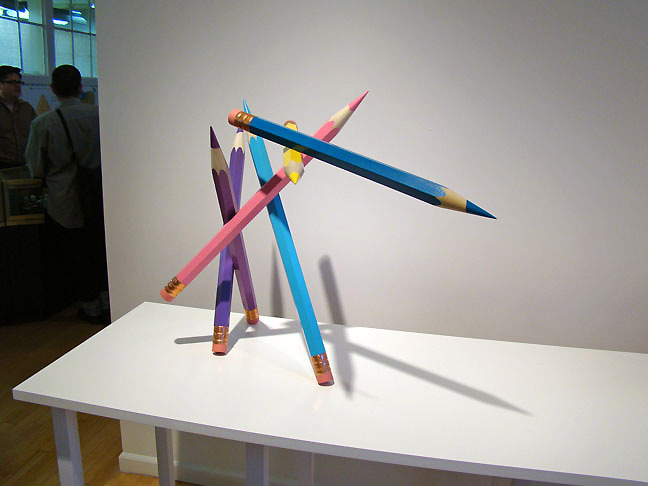

(oversized pencil sculpture by Bob Van Breda)

Current Features

- How to Buy Art on Instagram and Facebook

More and more people are buying more and more art online all the time, not only from artist websites or online stores, but perhaps even more so, on social media ... - Collect Art Like a Pro

In order to collect art intelligently, you have to master two basic skills. The first is being able to... - San Francisco Art Galleries >>