Breaking Into Art Auctions:

Make Sure You do it Right

If you're like most every artist anywhere, you've probably dreamed about having a work of your art go up for sale at a major auction house and watching the international art collecting elite battle over it with their bank accounts. The bidding is furious, the hammer falls, your art sells for a record price and the news goes viral. At last you've achieved that most elusive of all goals-- financial freedom for life-- the ability to auction your art whenever you need an influx of cash. From this point on, creating a work of art will be not much different than printing up money.

OK. Dreamtime over. The truth is that auctions don't operate this way. In fact, performance at auction can compromise an artist's reputation, collectibility, and price structure just as easily as enhance it. So before you try to turn your auction fantasies into reality, take a moment to learn about how this sector of the art business works. That way, if the opportunity ever presents itself, you'll be able to to maximize your chances for success.

To begin with, those record art prices the art sites write about and auction houses boast about represent only the tip of the top of the tip of all the art out there. For every work of art that's accepted by major auctions, many many more are turned down. And for every work of art that sells for a record price, many many more perform ordinarily at best. In fact, auction houses do everything they can to keep less-collectible out of their sales in order to minimize the chances of making the fine art marketplace look anything other than healthy.

Major auctions almost exclusively accept art only by artists with established track records of selling for substantial prices at major auctions. Yes it's a Catch-22, but auctions are in business to make money and they want to be as sure as possible that every piece they sell nets a certain minimum dollar amount. Depending on the requirements of a particular auction house or sale, that amount might be $5000, $10000, $50000, or more. If an auction has doubts about what the art might sell for, they probably won't auction it. And the best way to minimize doubts concrete proof that the art already sells consistently at auction as well as at galleries at or above those minimum dollar levels.

In the overwhelming majority of cases, artists who make the auction cut at the highest levels have had or are currently receiving so much publicity and recognition during the course of their careers, and especially concurrent with whatever sales they're being included in, that the mere mention of their names in press releases, auction announcements and auction catalogues is enough to attract plenty of private and institutional buyers to a sale. The demand for their art is typically equal to or greater than the rate at which they produce it (or the rate at which their galleries trickle it out into the marketplace), they've had numerous successful shows both at major museums and galleries, and the foremost critics, curators, collectors and other and art world professionals agree that the impact of their art on the art world is significant, at least at the moment.

More recently, auctions have expanded their focus to art by trending artists who happen to be white hot at the moment, and to specialty sales themed on whatever type of art is currently getting big press and currying favor among monied collectors. They may also stalk work by younger artists, unproven though they sometimes may be, particularly those with impressive online followings, and who are trending exceptionally well in the art media, both conventional and online. Some of the best barometers of hotness are how in-demand that art is, how fast it sells, how long the buyer wait-lists are, which famous collectors own it, how often they're getting written about, and how difficult it is to find quality examples for sale. Again, auction houses thoroughly research markets in advance so they can be as sure as possible that the art and artists will sell... and sell well.

With speculative buying more prevalent than ever, auctions also attempt to cash in on the actions of so-called investor/collectors. These buyers view art more as a commodity or "asset class" rather than as someting to enhance, beautify, and enrich the quality of their lives. They often do not buy to hold, but rather to flip for big profits later, at times reselling their art almost immediately after they buy it. But the parameters for auctions selecting this type of art remain basically the same as for that by older "proven" artists, which is that their publicity and name recognition are so widespread that their art, at least temporarily, is in a hyper-heightened state of demand.

For the rest of you artists, those with little or no auction experience, but with relatively consistent careers usually debut at lesser sales. Here again, an artist's resume, exhibition history, and name recognition have to be respectable as the auction needs some kind of evidence that their art stands a reasonable chance of selling for certain minimum amounts of money. The downside here is that in order to maximize the possibility of the art selling, the auctions often require presale estimates (price ranges they say suggest that art might sell for) to be significantly below the artists' typical retail selling prices.

For example, a piece of art that would normally sell at a gallery for $10000 might be estimated to sell for only $3000-$5000 at auction, perhaps even less. Rather than rely totally on the accomplishments of the artists to attract bidders, the auction houses tilt the odds of selling in their favor by offering the art at seemingly bargain prices. This strategy of estimating low is common among auction houses. For artists, agreeing to lower presale price estimates is usually worth the sacrifice if that's the only way an established auction house will agree to sell their art.

If you're lucky enough to make the cut, don't be insulted by this; be delighted and hope for the best. Getting your art into auction is anything but easy, and your first sales results are absolutely critical to establishing your credentials in the auction realm. In the meantime, do everything you can to maximize the chances not only of an auction house accepting your art, but way more importantly, selling it. In other words, continue to produce quality art, get shows at established galleries, do what you can to increase sales, and keep your name in the public eye.

A less common way that artists with little or no previous auction experience occasionally break into higher level sales is when their work is in famous collections or estates that are placed up for sale at auction houses in bulk. The biggest names in the collections draw the crowds as does the importance or celebrity of the collectors (like Warhol, Mapplethorpe, or John F. Kennedy, for example). Artists who make their auction debuts in this way tend to be presented not so much in terms of their own accomplishments, but rather as ones whose art the high-profile collectors considered significant enough to include in their collections. Regardless of how the auction represents the art, this is one way to get that all-important first shot.

However your art finds its way to auction (and it will usually be through third parties like dealers, galleries, or collectors), know that the large majority of selling prices fall within or slightly above or below the auction houses' presale estimates. Record or near-record prices, or sales that substantially exceed presale estimates are by far the exception. Also know going in that the large majority of art sells below what it would be priced at in retail galleries, so don't be disappointed if yours falls into that category. Except for major international high-profile sales filled with rare and highly important artworks, or in cases of isolated celebrity sales, auctions are little more than wholesale dispersals of goods. The good news is that knowledgeable buyers understand the difference between auction prices and retail prices, so don't worry if your art sells for somewhat less than your retail (in the 40-60% range or better is generally considered good). Worry if it sells for way less than retail or doesn't sell at all.

Keep in mind that whenever a work of art sells at auction, the hammer (or selling) price becomes a matter of public record. Sometimes even if the art fails to sell, that non-sale or "buy-in" is still publicly recorded. All auction sales results from significant regional, national and international auctions (currently in the vicinity of 300,000-500,000 total artworks per year) are published or accessible annually in online databases. Online databases include artprice.com, artnet.com, artvalue.com, artfact.com, findartinfo.com, liveauctioneers.com, and others.

Anyone can access these sales records at anytime-- sometimes for a fee, sometimes free-- and plenty of dealers and collectors do just that. Studying auction sales results helps them decide whether or not to buy particular works of art or to patronize particular artists. Experienced higher-end buyers tend to pay more for artists who consistently sell well at auction and tend to be cautious about or avoid those who have few or no auction records at all or who perform poorly or erratically. They also recognize that the greater the discrepancy between an artist's retail prices and auction prices, the weaker or less stable that artist's overall market tends to be.

In order for your art to stand a chance of being accepted at auction, you should be represented by at least one gallery, have a reasonably solid collector base, a good online following, a consistent sales history with steadily increasing prices, regular favorabile reviews in respected arts publications and websites, have been included in significant exhibitions at respected museums or institutions (regional, national or international), and most importantly, have some level of consensus from art world professionals that your art may be ready for auction and that it stands a reasonable chance of fetching a respectable price. The auction option is still worth considering without all of the above, but the fewer qualifications you have, the less likely the chances an auction will accept your art in the first place. If they do, the lower the presale estimate will be and greater the risk of it selling low or not selling at all. Neither of these outcomes is particularly good for an artist's career.

If you're still game for trying, begin auction inquiries by speaking with your galleries, dealers, or representatives. Hopefully they'll agree with you that approaching auctions is a good career move at this time-- and hopefully they'll be the ones to do it. Or that they'll be able to find someone known to the art and auction community to do it for them. (Don't think for an instant that you can do this yourself; auction houses do not normally accept first-time consignments directly from artists.) Whoever the consignor turns out to be, they should be prepared to present a reasonably solid case that your art will sell for whatever minimum price the auction house requires for its consignments.

That person should typically approach auction houses in locations where you have the highest name recognition and where your work is the most collectible. As for the auction itself, make sure they have someone knowledgeable about art on their staff, and that they have consistent success selling contemporary art similar to yours (you don't want your art consigned to a firm with no little or no experience or history here). If they conduct themed sales that consist exclusively of art by artists similar in stature and accomplishments to you, this is good. Whatever the circumstances, hopefully you have dedicated collectors who you can notify about the upcoming sale, a reasonable number of whom will attend and most importantly, bid.

Regarding the art itself, do your best to make sure that whoever approaches the auction house offers a more significant or better quality artwork for consignment. You may or may not have a certain amount of control over this. Good choices include a piece from a show that nearly sold out, one that was pictured in an online or magazine review or exhibit catalogue, one that's not easy to find on the open market, or one that's similar in composition to those works your collectors prize the most. You don't want the art to be anything other than that. Auctioning a mediocre example of your art can easily net you a mediocre selling price as well.

Even if your art sells below retail, the good news is that at least it sold. Hopefully, this will be the start of a longterm investment in your financial future-- the prospect of your art regularly selling at auction. So don't take it as an insult or slap in the face. To repeat, getting those first few sales records is the hardest, but once you've been "auction-tested," other auction houses will be more inclined to see you as marketable in their sales as well, and from that point on (assuming you continue to move onward and upward in your career), higher and higher auction selling prices will likely follow.

If your art fares reasonably well, avoid the temptation to go overboard and view auctions as a panacea. Over-consigning or giving collectors the impression your art is easy to come by is not a good strategy. In order for your auction selling prices to increase over time, you must continue to advance your agenda in traditional ways-- through gallery shows. and significant institutional acquisitions and exhibitions-- and use the auction option sparingly along the way. Because what happens at auction tends to mirror what happens in your career, good times to place an artwork or two up for sale might be immediately before, after or in conjunction with a significant museum or gallery show, if you expect to receive a run of publicity or a major commission, or at any other point when your career makes a noticeable move in the upward direction.

As your "marketability" improves, your art will likely be placed up for sale at auction by more and more people-- dealers, brokers, collectors, estates and so on. This process typically evolves over years and often decades from the date of the first sale, but sooner or later, consistent strong performance at auction becomes more or less self-perpetuating.

For those of you who have little or no hope of getting into auction at this time, one possibility is to approach a smaller local or regional house or even an arts organization with the idea of having a themed sale dedicated to art by local or regional artists. If you, your fellow artists and some dedicated supporters with a little clout in the art community can put together enough good art and convince the auction house or organization that attendance will be healthy and sales potentially good, this concept might work. But it won't be easy; you'll have to be persuasive. No matter what your approach, make sure you've got the support of those who buy, sell and collect your art before you test the auction realm.

Consigning to an occasional charity or fundraiser auction is also a decent way to get your feet wet, the keyword here being "occasional." Do not donate art to every fundraiser in sight; that could backfire by making your art seem too easy to buy outside of traditional venues like galleries. If your art sells consistently well at higher profile charity events, approaching an actual auction house at some point might be a good idea. To learn more about how to maximize your success at fundraiser auctions, read Art Auction Fundraiser Tips .

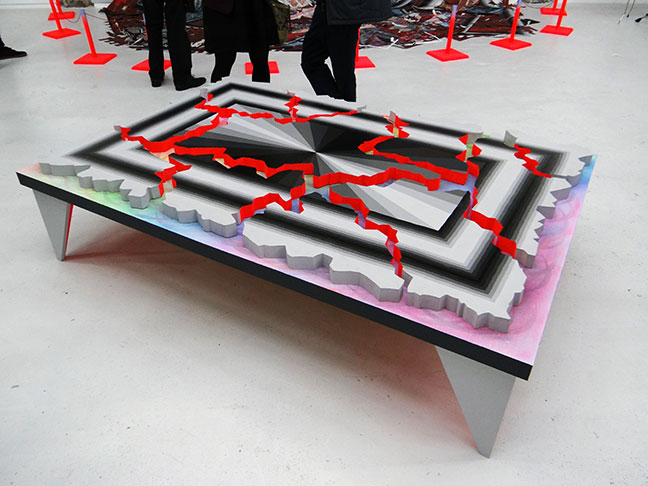

(art by Andrew Schoultz)

Current Features

- How to Buy Art on Instagram and Facebook

More and more people are buying more and more art online all the time, not only from artist websites or online stores, but perhaps even more so, on social media ... - Collect Art Like a Pro

In order to collect art intelligently, you have to master two basic skills. The first is being able to... - San Francisco Art Galleries >>