How to Save Your Art For

Retrospectives and Retirement

Q: I've been painting and sculpting for about twenty years and am pretty popular in my part of the country. I make art constantly, have sold hundreds of pieces and have hundreds more in storage at my house and in my studio. The bad news is that I'm kind of a pack rat and my wife gave me an ultimatum. She wants me to clean out the house and studio and get rid of whatever I think I can live without, including personal possessions and excess art. I'm thinking I'll probably get rid of mainly older art that I made when I was early in my career-- pieces I don't really care that much about anymore. Maybe I'll take them to a flea market and sell them for whatever I can get. What do you think?

A: This is a horrible idea. Do whatever you can to avoid selling even a single piece of your art (significant completed works, that is) at giveaway prices or worse yet, throwing it out-- especially earlier ones. Selling, giving away or throwing out personal possessions is one thing, but if you start getting rid of your art, you'll very likely regret it in the end. Over time, not only do individual works of art serve to document various points in the history of your career, but if you're purposeful about what you keep, that art can eventually become part of a lifetime retrospective. In financial terms, it can become like a personal retirement account or pension fund.

To begin with, you say you're thinking about selling or throwing out mainly earlier works. The facts are that the further artists advance in their careers, especially successful ones, the more collectors, dealers and fine art professionals tend to value and pay premium prices for earlier pieces rather than later ones. From a scholarly or documentation perspective, the same holds true for curators, researchers and art historians-- they tend to ascribe greater significance to earlier works because they often represent the formative stages of careers.

Anyone who understands how the art world works will tell you that once an artist has developed a mature style, a respected profile, and has become established in his or her career, earlier works become increasingly significant because they most clearly demonstrate how that mature style evolved. Earlier pieces are often considered to be more original, energetic, dramatic, risky, experimental, emotionally charged, and most importantly, they document artists' "growing pains." Later pieces, on the other hand, generally exhibit fewer such characteristics because the more successful and established artists become, the more the directions of their careers and art tend to flatten out and settle into more routine and comfortable production patterns. You younger artists may think this is all far far away right now, but sooner or later you'll fall into the "mature artist" category, and it's far better to learn about this progression the easy way now than to learn it the hard way later, and end up wishing you'd saved more early work.

For those who follow your career or are fans of your work-- both longtime supporters and recent converts-- the longer you're around, the more they'll want to know about everything you've accomplished and the more you'll come to realize the value of possessing evidence of every stage of your artistic development, especially the beginning. Simply put, a comprehensive record of your output makes your art easier for people to understand and appreciate, and involves them more deeply in your growth and evolution as an artist. So when it comes time to recount the good old days-- and sooner or later you will-- hopefully you'll have plenty of early art around to recount them with, and that includes having enough in your arsenal to throw yourself a respectable retrospective.

Coming at this from another direction, not everyone will always want to own only your latest creations or only care about what you're doing now-- especially as you advance in your career. Beginning and early-career artists commonly make the mistake of believing that whatever art they're making now is all that matters, all that their collectors care about or should care about, and that everything else is basically old, stale or irrelevant. As previously stated, not only does earlier work become increasingly significant over time in historical terms, but the more of it that sells, the less there is. Once it's off of the market and in private or institutional collections (hopefully including yours), you can never go back in time and make it over again.

In dollars and cents terms, increased scarcity is a component of value. Desirability is another component of value, and early work that is both scarce and desirable is almost always worth more than later work that is more plentiful and available. It's that simple and no more complicated. Which brings us to the financial benefits of saving your art. All you have to do is look at the lives and careers of famous artists and you'll see that those who set aside the greatest numbers of early works tend also have the greatest number of options later in life in terms of financial freedom.

Andy Warhol, for example, saved enough art for his beneficiaries to create an entire museum and foundation in his name-- art from every period in his career. On top of that, he was the consummate documentarian, recording or otherwise archiving practically every waking moment of every single day of his life (and sometimes even the sleeping moments as well). Other successful artists have used the art that they've saved to help establish and finance foundations or institutes, as inheritance for future generations, or as funding sources for research, grants or nonprofits. Many artists simply use the proceeds from the sales of saved works to support themselves in retirement once they slow down or stop making art altogether.

But back to you and your dilemma, in case you can't work things out with your wife and a certain amount of your art has to go, here are several suggestions:

* Whatever happens, separate out and keep your best early works along with comparably significant pieces from all periods of your career. These include ones that received distinctions or awards or coverage in the media, pieces that were created for special occasions, ones that represent seminal events in your life, ones that commemorate or that were created in response to significant incidents or periods in your life, and so on-- no matter how negative or difficult those events, incidents or periods might have been.

* Have several third parties who know and understand your art like gallery owners, longtime friends who really know your art, or similarly qualified art world professionals help you sort through your work first. They may recognize certain pieces as significant or worthy that you think are little more than afterthoughts or junk. Believe it or not, artists are not necessarily the best judges of their own work. Informed second and third opinions are often invaluable in situations like this.

* Save all materials that document your career such as exhibition catalogs, photographs, correspondences with collectors or galleries, formal contracts or agreements, sales records, show announcements and any other printed, recorded or video materials that relate directly to your art. Never throw anything like this out. Good documentation increases the value of art-- not only from scholarly and historical perspectives, but financially as well. Destroying any records of your artistic history will come back to haunt you-- guaranteed.

* If you can't afford to pay for storage, ask friends, relatives, associates or people with access to commercial spaces whether they'd like to display certain pieces of your art in their homes, offices or places of business at no charge or possibly as part of trade or exchange arrangements (free or low cost art for them; free storage for you).

* Ask people with storage space whether they'd be willing to store some of your art at no charge (or in exchange for a piece or two).

* Ask dealers or galleries that represent you whether they'd be interested in taking additional pieces on consignment, other than those you're keeping, including examples of your earlier work that you wouldn't mind selling (some might like that idea). You can also ask whether they'd be willing to store works that you're keeping.

* After setting aside your best pieces, have a studio sale and offer discounts of perhaps 20%-50% on whatever's left over. Then do what you can to find homes for the rest-- places where the owners will cherish and appreciate it.

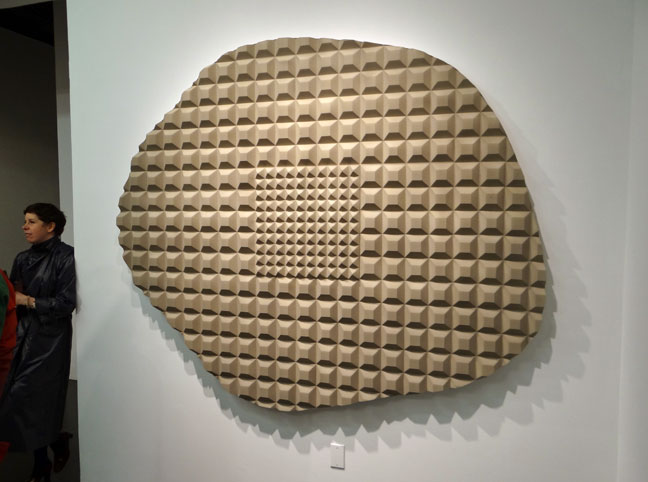

(art by Jacqueline Kiyomi Gordon)

Current Features

- How to Buy Art on Instagram and Facebook

More and more people are buying more and more art online all the time, not only from artist websites or online stores, but perhaps even more so, on social media ... - Collect Art Like a Pro

In order to collect art intelligently, you have to master two basic skills. The first is being able to... - San Francisco Art Galleries >>